LATEST ARTICLES

![TAIPEI and SHANGHAI -- Taiwan’s political class is nervous, yet again. I am in Taipei to speak on whether U.S.-China strains endanger Taiwan. I think not. Certainly, President Donald Trump, Shinzo Abe in Japan and Scott Morrison in Australia — three key countries for Taiwan — show no sign of reduced support. A slew of lesser Asian countries may hesitate to help Taiwan in a crisis, but all prefer a separate Taiwan to the island being swallowed into the People’s Republic. Such a disaster would bring the greatest change in East Asia’s balance of power since the second world war. Consider that during seven decades of Washington-Beijing ups and downs, Taiwan was unscathed. Today, the island is more prosperous and confident of its identity than ever. Its existence is a textbook case of deterrence working. Thanks, Uncle Sam and Japan. Economic stagnation on the mainland, which is quite possible, would not destabilize Taiwan. Political crisis in the mainland, much less likely, would harm Taiwan because of the flight of urban Chinese from Shanghai and other cities. Yet, leaving aside gyrations in U.S.-China relations and non-stop military calculations of both the PLA and Pentagon, demographic trends and tricks, and the stealth and reach of social media, could together destroy Taiwan as a democracy without a shot being fired. Population totals favor China. Russian people are a drop in the bucket alongside Chinese. Siberia faces a Chinese population surge, as Russia’s birth rate and economy lag China’s; Russia’s economy is one-eighth the size of China’s. Australia, with only 23 million people, may become a Chinese-flavored nation, as it once was British-flavored. Taiwan is more vulnerable than Russia, Australia or many others to demographic games. Sichuan Province (90 million) has four times the people in Taiwan (23 million). It would take only a tiny slice of the young males there, or equivalent numbers from Taiwan’s close neighbor Fujian Province (40 million), if “encouraged” by Beijing to go to Taiwan as “tourists,” then marry Taiwan girls — to produce a demographic reset of Taiwan’s democracy. No submarines or soldiers required Subjectively, one feels Taiwan’s vulnerability when flying from Shanghai to Taipei; from communism to capitalism — yet fewer minutes than a hop from Chicago to Boston. China cleverly uses the web to further a world future for socialist authoritarianism. Professor Hsu Chien-jung of National Dong Hwa University in Taipei began his research on Beijing’s electronic assault by asking a question: Why do huge numbers of Chinese individuals subscribe to Facebook when Beijing blocks Facebook for PRC Chinese? How many Americans know that millions of Chinese adherents to Facebook are physically in Taiwan? These selected “Taiwan folk” are a fifth column devised by Beijing. They spout Beijing’s policies to Facebook “friends.” Political influence is the tip of a seismic social iceberg. Culture and technology give youth new enjoyments, as they offer China new weapons. Reality looks different to teen-agers than to their parents; youth make their own reality and others will try to make it for them. “You may think you’re talking to a pretty lady or a handsome man,” says Mr. Hsu, “but it’s a robot somewhere, spitting out opinions.” With a new Chinese app called Zao, a kid may fix her head on the body of a sports hero or pop star and say whatever she likes. A “Jimmy Lai face” can opine day and night that Taiwan belongs to China (not the Hong Kong media magnate’s real view). Who speaks; Who listens? We don’t know, even in a world where anything goes and almost everything is presumed known. George Orwell wrote of Big Brother controlling a society. China could be a Global Big Brother electronically shaping international public opinion. Easy for selected Communist whiz-kids in Shanghai to reset minds, say in Vietnam, via the Internet. Much simpler than Beijing sending tanks and an army across the China-Vietnam border. A rising power is always tempted to push the envelope. The United States, like China, is an “unconscious empire,” often unwitting about its huge reach. Since 1945, Washington has trespassed on other countries in its own way. Today, timing offers China the Internet as a perfect tool to do the same and more. In recent years, PRC money has bought its way into Taiwan media. The Taiwanese newspaper the China Times, says scholar Hsu, “seems to be a representative of Xinhua [the CCP news agency] in Taiwan.” It is a giant step beyond print, to target individuals in Taiwan by invisible, deniable, anonymous electronic tricks. Reading a book or newspaper is an act initiated by an individual from below. The Internet, from above — from somewhere — makes the individual a target. Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen, who hankers for Taiwan independence, fears a huge, if under the table, effort to vote her out of power in January. True, the CCP has overreached before in its 70 years in power, regretting it later (and to be fair, fake voices are less horrible than real bombs). Beijing has shown with its Confucius Institutes that Chinese soft power can backfire. It may overreach on Taiwan, as it already did in Hong Kong. However, it is a fact that tidy millions of pro-CCP Chinese youth are in the world vanguard of IT. If this spooky stuff ultimately becomes a free speech issue, the West will prevail. If it is won on high-tech skill, not so clear. Internet attacks peacefully entering Taiwan living rooms 24 hours a day may consign submarines and soldiers to the museum. If this becomes the war of the future, asks Daniel Hahn in the Spectator, “can we ever have peace again?” Numbers and technology, linked, are a formidable weapon. • Ross Terrill’s books include “Mao” and “The New Chinese Empire.” His next book is “From the Bush to Tiananmen” (Rowman and Littlefield).](/images/b1-terr-taiwan-chin-c0-0-993-578-s885x516-x_small.jpg)

TAIPEI and SHANGHAI -- Taiwan's political class is nervous, yet again. I am in Taipei to speak on whether U.S.-China strains endanger Taiwan. I think not. Certainly, President Donald Trump, Shinzo Abe in Japan and Scott Morrison in Australia — three key countries for Taiwan — show no sign of reduced support. A slew of lesser Asian countries may hesitate to help Taiwan in a crisis, but all prefer a separate Taiwan to the island being swallowed into the People's Republic. Such a disaster would bring the greatest change in East Asia's balance of power since the second world war.

Consider that during seven decades of Washington-Beijing ups and downs, Taiwan was unscathed. Today, the island is more prosperous and confident of its identity than ever. Its existence is a textbook case of deterrence working. Thanks, Uncle Sam and Japan.

Economic stagnation on the mainland, which is quite possible, would not destabilize Taiwan. Political crisis in the mainland, much less likely, would harm Taiwan because of the flight of urban Chinese from Shanghai and other cities. Yet, leaving aside gyrations in U.S.-China relations and non-stop military calculations of both the PLA and Pentagon, demographic trends and tricks, and the stealth and reach of social media, could together destroy Taiwan as a democracy without a shot being fired.

Population totals favor China. Russian people are a drop in the bucket alongside Chinese. Siberia faces a Chinese population surge, as Russia's birth rate and economy lag China's; Russia's economy is one-eighth the size of China's. Australia, with only 23 million people, may become a Chinese-flavored nation, as it once was British-flavored.

Taiwan is more vulnerable than Russia, Australia or many others to demographic games. Sichuan Province (90 million) has four times the people in Taiwan (23 million). It would take only a tiny slice of the young males there, or equivalent numbers from Taiwan's close neighbor Fujian Province (40 million), if "encouraged" by Beijing to go to Taiwan as "tourists," then marry Taiwan girls — to produce a demographic reset of Taiwan's democracy. No submarines or soldiers required Subjectively, one feels Taiwan's vulnerability when flying from Shanghai to Taipei; from communism to capitalism — yet fewer minutes than a hop from Chicago to Boston.

China cleverly uses the web to further a world future for socialist authoritarianism. Professor Hsu Chien-jung of National Dong Hwa University in Taipei began his research on Beijing's electronic assault by asking a question: Why do huge numbers of Chinese individuals subscribe to Facebook when Beijing blocks Facebook for PRC Chinese? How many Americans know that millions of Chinese adherents to Facebook are physically in Taiwan? These selected "Taiwan folk" are a fifth column devised by Beijing. They spout Beijing's policies to Facebook "friends."

Political influence is the tip of a seismic social iceberg. Culture and technology give youth new enjoyments, as they offer China new weapons. Reality looks different to teen-agers than to their parents; youth make their own reality and others will try to make it for them. "You may think you're talking to a pretty lady or a handsome man," says Mr. Hsu, "but it's a robot somewhere, spitting out opinions."

With a new Chinese app called Zao, a kid may fix her head on the body of a sports hero or pop star and say whatever she likes. A "Jimmy Lai face" can opine day and night that Taiwan belongs to China (not the Hong Kong media magnate's real view). Who speaks; Who listens? We don't know, even in a world where anything goes and almost everything is presumed known.

George Orwell wrote of Big Brother controlling a society. China could be a Global Big Brother electronically shaping international public opinion. Easy for selected Communist whiz-kids in Shanghai to reset minds, say in Vietnam, via the Internet. Much simpler than Beijing sending tanks and an army across the China-Vietnam border. A rising power is always tempted to push the envelope. The United States, like China, is an "unconscious empire," often unwitting about its huge reach. Since 1945, Washington has trespassed on other countries in its own way. Today, timing offers China the Internet as a perfect tool to do the same and more.

In recent years, PRC money has bought its way into Taiwan media. The Taiwanese newspaper the China Times, says scholar Hsu, "seems to be a representative of Xinhua [the CCP news agency] in Taiwan." It is a giant step beyond print, to target individuals in Taiwan by invisible, deniable, anonymous electronic tricks. Reading a book or newspaper is an act initiated by an individual from below. The Internet, from above — from somewhere — makes the individual a target.

Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen, who hankers for Taiwan independence, fears a huge, if under the table, effort to vote her out of power in January. True, the CCP has overreached before in its 70 years in power, regretting it later (and to be fair, fake voices are less horrible than real bombs). Beijing has shown with its Confucius Institutes that Chinese soft power can backfire. It may overreach on Taiwan, as it already did in Hong Kong. However, it is a fact that tidy millions of pro-CCP Chinese youth are in the world vanguard of IT.

If this spooky stuff ultimately becomes a free speech issue, the West will prevail. If it is won on high-tech skill, not so clear. Internet attacks peacefully entering Taiwan living rooms 24 hours a day may consign submarines and soldiers to the museum. If this becomes the war of the future, asks Daniel Hahn in the Spectator, "can we ever have peace again?" Numbers and technology, linked, are a formidable weapon.

• Ross Terrill's books include "Mao" and "The New Chinese Empire." His next book is "From the Bush to Tiananmen" (Rowman and Littlefield).

WASHINGTON TIMES, Oct 23, 2019

STALIN AND MAO: A Comparison of the Russian and Chinese Revolutions Lucien Bianco Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2018 xxv + 448 pp. $65.00

By Ross Terrill

This rich and welcome book is less a dual biography as the title announces (Stalin and Mao) than a study of the Russian and Chinese revolutions, following its subtitle (A Comparison of the Russian and Chinese Revolutions). A painstaking study, by a veteran Sinologist who recently devoured (non-Russian language) material on the Soviet Union, it is well translated from the French. Here is a sad and gripping story of strong-man leadership, failed hopes, national triumph, destruction, needless famine, retribution and exaggerations of what politics can deliver.

After a rewarding Foreword by another French scholar, Marie-Claire Bergère, there are two comparative Russia–China chapters, "Laggards" and "Catching up," to set the scene of pre-revolutionary conditions. The next seven chapter titles have a textbook feel that betrays a limitation within them: on few of these topics (baldly named Politics, Peasants, Famines, Bureaucracy, Culture, Camps, Dictators) is Bianco able to stick to comparative argument.

The author states his key theme: "To get the measure of Mao's thoughts" we go to the "Stalinist model," codified in the Russian's Short Course of CPSU history (p. 70). Some may doubt whether Stalinism is the full measure of Maoism, since Mao was the Marx–Lenin–Stalin of the Chinese revolution.

Bianco revels in the startling nugget, quick opinion, detour to European literature, and (once) a regrettable insult that a certain Mao biography (not mine) "contains only lies" (p. 406). But much of the book is a casserole of learning, experience and anecdote that is a pleasure to read. Bianco acquaints Sinologists with We by Yevgeny Zamyatin, who wrote to Stalin: "I have a bad habit of not saying what is my interest to say, but what seems to me to be the truth" (p. 240).

It's priceless that "mass movements" so beloved of Mao, were labelled "organized deception" by Bukharin not long before his execution (p. 73). An entire volume could be written on "Mao's organized deceptions."

One of the author's frequent moral balance sheets salutes Mao for sparing Deng, a "confirmed sinner," for a second innings. A "Russian Deng" would not have outlived Stalin, as Deng, to China's good fortune, outlived Mao by 21 years. A Chinese Bukharin could have lived, thrived post-Mao, and told his grandchild, hunched over her smart phone, of nasty deaths in the Cultural Revolution (p. 314). Of course, being reversed later seems a perverse way of exonerating Mao for letting Deng survive.

Disappointing that Bianco lacks space to fully analyse the two lives. Did Stalin's theology education – barely mentioned – mean nothing for his mind? How can Mao come alive without his sons, daughters, four marriages and staff who saw realities about the boss that colleagues didn't? Li Min's Wo de fuqin Mao Zedong (My Father Mao Zedong. Beijing: Renmin chubanshe, 2009) could alone have enriched some of Bianco's points.

Mao's journey from his pro-individualism views of May Fourth to Leninism by the late 1920s explains his post-1949 rule, but Bianco squeezes all Mao into Stalin's "older brother" mold, which only fits Mao later; Short Course first appeared in 1938. Had Bianco done his study of Stalin and the Soviet Union not before, but during or after decades of expertise in China, his Mao may have looked less Stalinist and more an eclectic bundle. Careful readers will look in vain for "younger brother" Mao's judgment of his "older brother" after the latter's death: "In my entire life I have three times written in praise of Stalin. In Yan'an on his sixtieth birthday. In Moscow on his seventieth birthday. And when he died. None of this was done willingly – I had to say these things" (in Wu Lengxi, Shinian lunzhan, 1956–1966: Zhong Su guanxi huiyilu [Ten-Year War of Words, 1956–1966, a Memoir of Sino-Soviet Relations]. Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian chubanshe 1999, 20).

Bianco says his book was written in 2013 (p. 67), before Xi Jinping began his post-Deng era, and critics will say that Xi, leaving both Stalin and Marx in the dust, has shown the centrality of Beijing's ongoing Leninism. Xi's tight rule is matched in Cuba and North Korea. What do Cuba's political system and North Korea's have in common, but Leninism? What did Mao and Stalin have in common: mostly Leninism. The cultures of these four countries are so various that political theory must explain their politics.

Bianco gives us erudite, sharp-tongued, mischievous, meandering and occasionally contradictory asides. Excellent as expected on rural life, with carefully obtained figures and revealing demographic analysis, he seems less sure-footed on Stalin's and Mao's political thought. He mentions the efforts of senior colleagues to get "the revolution back on track" after the GLF, but on the next page says both Stalin's and Mao's revolutions were "enterprises condemned from the start" (pp. 11–12). "On track" is unclear. Bianco never really argues that Marxism–Leninism was mistaken in fundamentals. "Mao did at least dream of equality," he writes, taking Mao's side for a moment, "whereas Stalin rejected it." But Mao was at his worst when ordering his dreams implemented. "I have allowed myself to be monopolized by Stalin's influence on Mao," the author confesses late in the book.

When researchers from a Beijing economic think tank visited Harvard in 2018, I asked the leader if class struggle exists in Xi's China. Vigorously, he declared: "Mao's class struggle talk was utter nonsense from beginning to end." Bianco never argues in sustained fashion that Mao concocted class struggle for power purposes. But the book often implies it. Other times Bianco takes Mao as utterly cynical and insincere, even "insane," making "steady" Stalin look good.

The book is important in departing from Fairbank's stress on the CCP's Chineseness. As a graduate student at Harvard, I fell under this Fairbank influence – that Chinese culture made Mao's Communists a different beast from the Soviet's Communists. Bianco's book challenges the China-uniqueness school. At Harvard we also overestimated the importance of Mao and other semi-intellectual Leftists being from farm backgrounds. Bolsheviks had no experience of peasants before 1917; CCP intellectuals did, some for years. Yet this book finds only minor differences in outcome between Stalin's and Mao's throttling of agriculture to speed industrialization.

Bianco pulls fewer punches than in his previous works. The 1930–1934 famine in Kazakhstan killed a third of the Kazak people, he writes. Areas of Ukraine known to be naturally fertile – you could put a stick in the ground and watch it grow – met disaster. "Stalin mercilessly squeezed the peasants and in doing so killed them. Mao killed as many, if not more, by ignorance, arrogance, and insanity." Passages on science and culture under Stalin and Mao are hardly less dire. Russian scientists secreted American research papers within fake Russian covers. In Moscow zealous parrots died old and covered in medals (p. 231). A Chinese prisoner is eliminated as a "stinking capitalist" because he cooked a rat to eat (p. 283). In both countries, acts of kindness punctuated the horrors.

The poet Maximov cries out: "The whole world, the entire universe, should bless Russia to the end of time, because she has shown, through her atrocious example, what must not be done!" Bianco fires a shot: "What a pity that China did not learn that lesson" (p. 243).

Some readers may find Bianco's moralism edging out calm reasoning. Calling his two protagonists "Monsters" grows limp after twenty-odd outings. Moral balance sheets of Stalin's and Mao's evil yield few conclusions. Perhaps shocked at himself, the author, at regular intervals, reminds us that Mao improved health, education and mortality rates. Alternation of curse and apology does not help readers see broad patterns, but it is honest and shows Bianco's humanism.

Bianco has an engaging way of asking the reader to think along with him as he juggles passion and reason: "No, I'm being unfair"; "I should mention at the very least"; "I was about to say"; "I shall begin the impossible demonstration…"; "I can't be content with the spontaneous sarcasm I have allowed to slip through…." He brings himself in: "To discern what was Marxist and what was Han in Mao, I only need to refer to myself. I could keep repeating the standard clichés about Confucius, but he will always remain less familiar to me than Socrates, Montaigne, Pascal…" (pp. 69–70).

It is at once a charm and a frustration of the book that Lucien Bianco admits to more missteps than he actually makes: "I have endeavored to attach Mao to Stalin, but let us not forget to attach both of them to their common source" (p. 76). An afterthought? Surely much more. Lucien Bianco advises, "If at all possible, it is best to avoid revolutions altogether" (p. 350).

He favours Russia on post-revolutionary post-mortems: "Maoism, the Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution certainly merited a Shakespeare, a Tolstoy, or a Dostoyevsky… To truly understand totalitarianism in its Communist version, and therefore the 20th century, we will be eternally grateful to the Russians and not, or not yet, to the Chinese, who lived through the same tribulations" (p. 246).

Ross Terrill

Last century, when Mao ruled China, shop assistants repeated daily, ‘We don’t have any more’ (Meiyou). I heard the phrase when asking for fish in a fishmonger or sausages at the butcher’s. This Mao-era chime meant ‘We don’t care a bugger.’ Six girls in a row would chirp Meiyou like a catechism. Unvarying. Maddening. Eyes were on the boss, not the public. The customer was always wrong.

In 2018 tech-fed millennials and teens, more savvy than in most nations, love the phrase ‘Just a moment’. More likely it’s 30 moments. You want a taxi to the dentist? ‘Just a moment.’ Forty minutes later with a galloping toothache, you scan the traffic for a Didi or a limo. Under Mao no one cared about commerce. Under Xi few in urban China have time to care about anything, except money.

Heedless ones today are the small kids. Being mostly the only child in the family, the little one can do no wrong. At breakfast in the Jianguo Hotel a boy of 8 or 9, already fat, swallows an omelet; noodles follow. He pauses only to kiss his mother. She interrupts talk with her husband. Two pudgy hands grab her cheeks. The boy resumes his chopsticks and pushes chunks of cantaloupe into his mouth.

This week Wang Shaoguang, a longtime bigwig in the western province of Guizhou, was dismissed ‘from all posts’. His taste for golf and orchids ate up government funds and ‘politically improper foreign books’ muddled his mind. My publishers seem alert to the message. A table in their smart new lobby groans with titles on or by Karl Marx. In ten minutes no one stops at it. I thought of Mr Wang in prison with his orchids (maybe not). In China today, Wang’s improper foreign books and my publishers’ selection of proper Communism books fight it out.

Anhui, a modest province inland from Shanghai, boasts a School of the Gifted Young. I hear shocked cries from education gatekeepers in Australia and USA. We need Safe Places on our campuses! Not a talent struggle red in tooth and claw! Youths left behind will feel hurt! Those admitted to the SGY must first pass the gao kao (national university exam) years ahead of their age. Doesn’t opportunity feed on opportunity? Of course it does. And excellence spurs more excellence. And China surges.

Some foreign leaders speak rudely of Belt and Road Initiative, a nebulous plan now sometimes called China’s ‘connectivity project’. The Malaysian PM said he fears a ‘new colonialism’. A senior Chinese figure crisply reminded the ‘summer Davos’ in Tianjin last month, ‘Belt and Road Initiative is not a Chinese Marshall Plan.’ The money we pour in isn’t ‘a free lunch,’ he added. ‘We expect a reasonable return.’ The debt of Pakistan and other receiving countries rises by the month, and Belt and Road’s geographic reach expands like the waistline of Kim in Pyongyang. Last week Xi drew far-off Samoa into its orbit while welcoming its leader. Our new foreign minister might ask her Chinese counterpart: Name one nation on the planet that isn’t potentially part of Belt and Road. If there are none, that would make this ‘connectivity project’ startling. Retaliation for Western empires, perhaps?

Did two teenagers fool around 36 years ago after drinks at a Washington high school shindig? American left-wing media and their masters in the Democratic party weep that one boy may have planted an unwanted kiss on a girl. Outraged eggheads on CNN sound like a gaggle of schoolmistresses. A Chinese student watching asks me, ‘Don’t they care about the trade war?’ Silly us. We forgot that a virginal high school record is vital to fitness for the Supreme Court.

I am to speak at the Nishan Forum on World Civilisations in Qufu, where Confucius was born. My topic is tough: ‘Will American civilisation and Chinese civilisation clash or co-exist?’ Nishan is the ‘philosophic heartland’ of China, theprovince governor tells us. A professor declares, ‘Nishan is to China what Rome is to Europe.’ In Benevolence Hall of Grand Learning within a magnificent palace, carved statues of Confucius’s 72 disciples gaze down from vaulting walls. At forty tables carved from local wood, forty little boys brush-draw Chinese characters, supervised by forty calligraphy teachers.

Before the Nishan Forum ceremonies begin, a stark contrast to the ethics mood brings a hedonistic documentary. ‘A Better Life’ shows girls in bikinis on a beach playing volleyball. Boys holding beer mugs join them to pluck peaches from succulent green trees. This is the ‘happiness’ promised by Xi. ‘Your future is in your own hands,’ Confucius and Xi both preach. Volley-ball in one hand, peach in the other, it sounds great.

Xi’s idea is that Confucianism will keep folk quiet and disciplined (social stability), while the Communist party handles the big stuff (political decisions).

‘Westerners say one’s own judgment eclipses everything else,’ complained a Chinese professor. ‘But Confucius said the individual cannot be separated from history and tradition.’ China’s greatest thinker would not pull down statues or trash old sports photos that lack females. Still, Deng pulled down thousands of Mao statues after 1978. It’s not a monopoly of the social justice crowd in the West, to bury history in the name of today’s ‘truth’.

Confucius’s ideas spelled out in the forum impressed some of the sprinkling of foreigners, including me. Sky (father) and Land (mother) as the wellspring of a religion beats the hell out of jihadism with its bombs and suicide murderers. But Beijing should go easy on using Confucius for political or nationalist reasons.

How will Beijing square its insistence on regional boxes with the amazing reach of Belt and Road? Daily, Chinese officials and scholars say ‘countries outside the region’ should keep their distance from the South China Sea. They correctly say, ‘Japan is not a party to any of the disputes in the South China Sea’ and Tokyo is quite far off. But Beijing disregards ‘regional’ boxes when convenient. China is busy all over the South Pacific, but China does not share a region with Papua New Guinea or Vanuatu. Australia does. Will Beijing respect Canberra’s higher claims in the South Pacific? Who from outside the region (if anyone) should poke their nose into the South Pacific?

Happily, Premier Li Keqiang seldom plays games with regional boxes. He likes the ancient maxim, ‘You can’t have fish in addition to bear’s paw.’ Li understands the trade-off between the irritating Number One role of America in the world and the value to China of an East Asian security order led by the US.

SPECTATOR AUSTRALIA, January, 2018

Letter from Beijing

Confucius casts his shadow over China’s latest emperor

ROSS TERRILL

Political extravaganzas in China, like October’s 19th Communist Party Congress, aren’t policy turning points. They are theatre. Only one of the last dozen such performances heralded a new course: when Deng Xiaoping in 1982 subtly buried Mao’s leftism. Party congresses are opera with plumes and feathers. High notes in tonight’s arias hide low notes in yesterday’s skullduggery.

Walter Bagehot, in 19th century Britain, said government comprises a dignified part (monarchy, Lords) and an efficient part (parliament, inky wretches of the press). China relives this duality in the 21st century. Lately, Beijing has found a novel – not yet efficient – way to influence Australian policies by enticing Sam Dastyari, Bob Carr, and other notables willing to parrot China’s views.

In Beijing, locked-down for the ‘19th Da [Big One]’, as Chinese dubbed this Congress, state and society were apple and banana. In newspapers, TV, and slogans on fences, the state declared the ‘historic’ and ‘brilliant’ Big Da would anoint Xi Jinping and his ideas. Few listened.

The city works well, but politics is absent from daily life. Chit-chat is about traffic, prices, health (‘Don’t forget your mask, darling’) and unsafe baby food. The red hot state, inside the ill-named Great Hall of the People, leaves a bored populace cold. The official public philosophy of Marx-Lenin-Mao-Xi is a distant mountain, seldom visited, its message lost in a buzz of money-making below.

Class determines politics, left-wing professors told me years ago. But decades of Mao’s rule from 1949 produced no middle class. Nor are class relations the key to China’s recent success. Rather, an undefined state-society link sees business groups and others in murky deals with government. This hybrid dish is recently spiced with Confucianism. Never mind that Mao said, ‘I hated Confucius from the age of eight.’ Xi doesn’t hate Confucius; he finds the sage morally useful.

Confucianism over millennia viewed society as one big family, with the emperor or as father figure. Forget heaven and the after-life. Confucius declined even to discuss an ‘after-life’. The Chinese state often repressed transcendental religion, but not Confucian social-religion. Confucian norms favored community over the individual. Function outweighed intrinsic rights. Today as under the dynasties, authoritarianism reaches down as neo-Confucian social-religion gazes up.

Crucially, China’s economy flourishes without the West’s public-private division, and without the West’s civil society separate from the state.

The former Harvard economist Alexander Gerschenkron said ‘late developing’ countries use state power to catch up with early capitalist modernizers. It’s true of China. Because Chinese tradition emphasised community and social responsibility, it suits the late-developing Deng-state. China has organisational resources, thanks to Mao’s unifying hand, and financial capacity, thanks to Deng’s open door, to match the USA and Japan.

Individuals, not taken seriously by the state unless they step out of line, are permitted to choose apolitical lives, opting to be capitalists, Christians, or jet-setters to New York and Paris. The state generally allows this. Marx’s idea of class is irrelevant. Xi and China’s billionaires share one continent-sized bed.

Citizens are members of society not primarily through government dealings (none vote), but as consumers at shops and businesses; employees (some in a joint venture with foreigners); families doing transactions with rural relatives; members of a church or cultural club.

The state allows initiatives from below on a trial basis. ‘Getting on the train before purchasing a ticket’ is the street slang for bold business activities which benefit from vague laws and seek a government rubber stamp later. This cheeky practice furthers economic growth, while reducing the danger to bureaucrats if growth disappoints.

Here, ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics,’ which Xi chose in October as his ruling motto, finds its meaning. ‘For a new era,’ Xi added to the motto – broaching a future, ominous for Washington and Canberra, when Chinese ways will be universal ways. But the set up breeds corruption. And its rationale triggers China’s cocky treatment of Australia recently.

The CCP acknowledges reduced trust between Party and people. This cries out for less state suspicion and eavesdropping. Society wants more room to breathe. The 1.4 billion Chinese people hold varying views of socialism – not just Xi’s view.

Confucian social religion should be part of Xi’s China Dream. The official state ideology surely has outlived its once-inspiring purpose.

Instead of elevating Xi to Mao-status in the party constitution, as the 19th did, Beijing should set out principles of socialism without giving the package an heroic or teleological label. It would draw on the social-religion of Confucianism, just as the US constitution and British common law draw on values of their societies.

Xi Jinping has tightened the partystate. ‘Wherever the Party goes, you must go,’ he declared to soldiers at the PLA’s 90th birthday celebration, and similarly urged ‘absolute loyalty’ on the media. He pushes foreign joint ventures, Disney in Shanghai among them, to allow Communist Party cells in their factories, and hold meetings (of Disney’s 300 CCP members) in factory rooms during work hours.

Before long, China may install a leader from a Buddhist family (as Mao was) or one who has lived years in the West (as Deng did). Possibly a Trump-like figure whose background is business, or even a female Christian. Any would signal a landmark for the autonomy of Chinese society and Confucianism’s role.

Without exception, China’s Communist leaders, from Mao to Xi, have all been lifelong politicos. Skullduggery, not opera, has been their trade. Yet China is the most money-minded major nation in today’s world!

Soon we’ll know whether Xi, inflated by the 19th Congress, will soar as a tyrant, or take the next ‘reform’ step beyond Dengism, matching economic freedom with political freedom. I am not optimistic, short term.

The day after Deng died in 1997 I wrote an oped in the New York Times which the editors shrewdly headed ‘The Last Communist’. The little chain-smoker indeed ditched Marxism. But he kept Leninism. So does Xi. Prosperity, Globalisation and Confucianism should give Beijing a chance to finish the dismantling. But jettisoning Leninism might rock Mao’s state. That risk must frighten Xi.

Ross Terrill’s books include ‘Mao’, ‘Madame Mao’ and ‘The New Chinese Empire’.

SENT TO NYT, JANUARY 2, 2018:

Dear Editor,

Are journalists accountable, or do they simply make politicians accountable, while trying to decide elections in the media? Ross Douthat is a thoughtful writer but on Sunday he was illogical. He uses “confession,” “mistaken” “folly “but he cancels any mea culpa by writing, “Now is a good time for intellectual humility, and for reserving judgment.” Why wasn’t it also a good time in 2016-17? Douthat wrote, “If Trump is the nominee, neither Rubio nor Cruz will endorse him.” Wrong, “To support Trump for the presidency is to invite chaos upon the republic and the world.” One awaits Douthat’s confession to that overkill; nothing less than trying to rob voters of their role. But “now,” Douthat gives himself an extension: “Keep your powder dry,” he cries. One must await the entire Trump presidency before evaluating it. Impossible. It’s not over. His piece is not a “confessional column,” but an attempt to justify his investment in Never Trump with hedge-your-bet pessimism. He slides to safety by changing the subject to Obama and the debt. Kicking the can down the road three years is not an accounting.

- Ross Terrill

March 25

In The Australian Primrose Riordan’s story has Stephen Fitzgerald claiming, “Australia would have no influence with China unless ties were strengthened with Asia’s superpower.” Dubious. Successive recent governments of both parties in Canberra have rightly and enormously strengthened ties with China. But Premier Li’s warning "against siding" with the USA is a red herring. The surest way to lose leverage with Beijing would be to pull away from Washington. Read John Howard’s memoir. He found the US alliance “no impediment” to China relations, but actually increased our leverage with the Chinese. Alan Thomas, another former Australian ambassador in Beijing, found the same: “The Chinese were particularly interested in us because we’re an American ally,” he said in an interview.

LETTER TO NEW YORK TIMES

Dear Editor,

Your Saturday Profile on Chinese medicine is acute and thoughtful, as expected from Ian Johnson. Dr. Unschuld’s juxtaposition of “rigor” and New Age puffery is salutary, but “Chinese pragmatism” hides a few things. Mao Zedong called for “walking on two legs,” not being one-sided. As Unschuld scorned herbs and acupuncture for his own bilateral lung embolism, Mao mixed praise for Chinese medicine with hard-headed preference for Western medical science on his own body.

Like Mao, James Reston adopted pragmatism, which isn’t very different in China from America. For the columnist’s appendix surgery in Beijing in 1971 the anesthetic was a standard injection of Xylocain and Bensocain. Reston used acupuncture only for lingering pain afterwards. Mao said Chinese medicine was one of China’s three great contributions to world civilization (together with the game of mahjong and the novel Dream of the Red Chamber), but his doctor, Li Zhisui , reports that he preferred Western drugs and surgery.

In China and elsewhere I have found acupuncture good for migraine and pointless for hip arthritis. Unschuld is a voice of reason and Johnson delivers it beautifully.

The German scientist believes medicine and politics are similar. “You don’t blame others, you blame yourself… What did I do wrong? What made me vulnerable? What can I do against it?” This message may touch America’s own politics in 2016.

Ross Terrill

Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies

Harvard University

LETTER SUBMITTED TO NYT, 12/12

Dear Editor,

Nicholas Kristof bravely faced down the campus echo chamber yesterday. His quotes from Cass Sunstein on judges reinforcing each other in like-minded groups are especially telling.

Upon Bush’s re-election in 2004, the Fairbank Center at Harvard held a panel on the outlook in Asia for the president’s second term. Amusingly, five Democrats were chosen to answer the question. None of the Republican Asia specialists (I was advising Vice-President Cheney then) were asked to be part of the predictable monologue. Students eyes glazed over.

Eyes would and should glaze over if

five Republican Asia specialists were to be asked the same question in 2012

about Obama’s second term.

Dec 5 it was much the same at the Fairbank Center as a panel tackled

“Trump and Asia,” No one from Trump circles was on the panel. The unfairness of

this – one grows used to it – is not as bad as the flouting of pedagogical

method.

At their best professors at Harvard and at University of Texas, where I taught, required

students to study both sides of an issue, from primary sources, then present

their conclusion. Isn’t that what education’s about?

John Stuart Mill in “On Liberty” urged a “clearer perception and

livelier impression of truth [that is] produced by its collision with error.”

That collision is a university’s mission. But there’s no collision if only one side is represented.

Ross Terrill

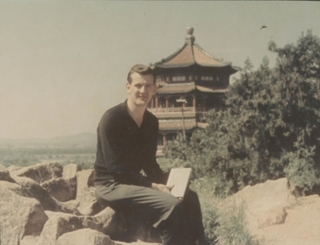

Rupert Murdoch’s flagship newspaper, “The Australian,” asked me to write a memory of the paper’s origin. Here is the start of my essay - about writing 6 articles for Rupert after a trip to China, fifty years ago. The full essay can be read from this link:

December 1, 1964

China's future

Ross Terrill writes: A tendency exists to think international problems get steadily worse, but 1964 was more troubled than 2014. All of East Asia was immensely poorer than it is five decades later. Tumult beset the truculent Soviet Union, as Khrushchev was kicked out as Stalin’s successor. China exploded its first atomic weapon in 1964. In Beijing and Guangzhou, photos of Chinese children cheering at the news of President Kennedy’s assassination nine months before made me fearful for US-China relations. But of course not all Chinese believed what the party-state told them. In Beijing, short of funds, I went to the British Office, which represented Australian interests. They lent me 15 pounds. I was a novice of 25 who knew little of China and no Chinese but here is the last paragraph of my sixth article 50 years ago: “All around the world, from Singapore to San Francisco, you can see pockets of Chinese society, but only in China can you grasp the formidable civilization in old and beautiful setting. Only in China do you realize what the Chinese as a race and a nation must increasingly mean in future decades. Just as once in the past, long before the present barren era of clashing ideologies and wrenching divisions, China was the greatest power on earth, so in the future she may become so again.”

IN a Shanghai hotel room during a conference last month on the art of biography, I sat down to polish my speech on Mao for the following week at the National Library of China in Beijing, but my laptop announced an email from my Chinese publisher cancelling the event. "Fluctuations in the Reputation of Mao over 40 Years" was "too sensitive", the government told the National Library, host of the book-signing for the Chinese edition of my Mao: A Biography. The publisher explained: "Mao's 120th birthday is at hand."

Why is Mao sensitive 37 years after his death, 22 years after Deng Xiaoping buried his political ideas and turned China from communist dinosaur to prosperous rival of the US?

Because Mao is the Marx, Lenin, and Stalin rolled into one of China. He was philosopher, armed insurgent and socialist planner. Dead in 1976 yet not departed. His mystique does duty as China's constitution. Ultimately, Mao is required since no electoral legitimacy has updated Mao's conquest of power by the gun in 1949.

The area around Shaoshan, Mao's home town, is spending $3 billion for the 120th anniversary, which falls today. A choir of 10,000 will sing of Mao as the Rising Sun and another 10,000 will quaff "auspicious" birthday noodles at hotspots of Mao's revolution. China Post has issued commemorative stamps, "100 Moments of the Great Leader" have been captured in clay sculptures, and 20 master craftsmen spent eight months on a golden statue inlaid with gems worth $16 million in the southern business mecca of Shenzhen.

Nevertheless, a 100-episode TV documentary on Mao was suddenly cancelled and another long-planned birthday event, "Reddest is the Sun and Dearest is Chairman Mao", has been renamed "Singing for the Country: A New Year's Gala" and the poster for it changed from a portrait of Mao to one of the Great Hall of the People venues. President Xi Jinping warned that celebrations must be "solemn, austere and pragmatic", confusing many.

Pop stars use Mao's words for lyrics, taxi drivers hang his portrait on the steering wheel to ward off accidents, artists reinvent his moonface, farmers clutch his image when Yangtze floodwaters surge, smokers toss unlit cigarettes on to Mao's old wooden bed in remembrance of one who chain-smoked, a Shanghai department store uses Mao as mannequin for pricey silk pyjamas.

A millionaire from Anhui Province wrote to me inscrutably after reading my book: "The more money I get, the more I feel nostalgia for Mao." Nikita Khrushchev attacked Stalin in 1956 and the Soviet Union never recovered. Deng didn't attack Mao in the late 1970s; he declared him 70 per cent correct and 30 per cent wrong and replaced politics with economics. The PRC thrived. Bread and circuses won the day.

Yet these ingenious solutions to Mao's shadow - slice him into good and bad; push him into the netherworld of Chinese folklore to join the Yellow Emperor - don't cancel Mao in the way Russia and Germany cancelled Stalin and Hitler. Xi obsesses over why the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 despite Moscow's efforts to finesse the Lenin-Stalin system. That catastrophe haunts him as he caresses gross domestic product figures, strides the world stage - and fumbles Mao's 120th celebration. During the Shanghai conference on biography, two scions of famous political families regaled me with comments on Mao. The son of a colleague of Zhao Ziyang, who fell from grace with Zhao after Tiananmen in 1989, praised a vitriolic book, Mao: The Unknown Story (banned in China), for saying Mao was utterly lacking in human feeling (ren qing). The son of a leftist leader of the 1970s who fell after Mao's death differed: "I believe Mao's ideas should have a role in China today and in future."

Just as lively were journalists' interviews after the conference. "Are there any questions you won't answer when you come to China?" began a young reporter from Southern Weekend. None, I said, wondering if he was going to ask me if I was gay. He pushed ahead: "When I compare your Chinese Mao with the English, I notice differences. What did the Chinese cut out and why?"

Still, Mao is less radioactive than at his 100th birthday. Then-leader Jiang Zemin unveiled a 10m statue of Mao at Shaoshan and made a fuss over Mao's grandson. Rasped the semi-retired Deng: "Who's behind these festivities?" Jiang was gently using Mao to build his own post-Deng legitimacy. A calendar in Shenzhen expressed Deng's Delphic view: "Remember Mao Zedong and Be Grateful to Deng Xiaoping."

Mao predicted tension among his successors. "Rightists may well use what I have said to keep in power for a time, but leftists will organise themselves around other things I have said and overthrow them." Today, economic reformers like Premier Li Keqiang feel no need to mention Mao's name. Xi, who does cite Mao, must fear the Left or see value in placating it.

Who is behind the festivities indeed! Any boss of the party-state must pay obeisance to Mao as long as the Communist Party rules. Those few leaders who seek real political change are bound to be irritated at the festivities. But Mao's grandson and other leftists urge Xi to proclaim today a national holiday, Mao Zedong Day. Wouldn't this flesh out Xi's "China Dream"? A taxi driver saw a Chinese pragmatic solution. "Why does a man dead 120 years have to have a birthday at all?"

After the National Library caved in to government pressure. the Capital Library took over my event and a huge crowd turned up. The chairwoman said questions weren't possible. I objected and she compromised by allowing people to write down questions, from which she gingerly chose three. Looking relieved when the session finished, she handed me a red envelope of Chinese banknotes. The book signing began. One man holding a small boy in his arms whispered as I signed his copy: "Was Mao an emperor?"

Ross Terrill is the author of The New Chinese Empire and writes from Harvard's Center for Chinese Studies.

Ross has an Oped, “Obama must stand by Japan over Senkakus” in Australian Financial Review, March 5

ROSS'S NEW ARTICLE LOOKING BACK AND FORWARD ON NIXON'S OPENING TO CHINA, 40 YEARS AGO

The spectator australia | 9 July 2011 | www.spectator.co.uk/australia vii

Richard Nixon, a geopolitician, visited

China to tilt a balance of power unfavourable

for Washington, eventually

facilitating an economic golden age in Asia-

Pacific. Gough Whitlam, a liberal internationalist,

went to China to promote a role for Australia

in a hoped-for multipolar world to follow

the Vietnam War. The two approaches

meshed better than either Nixon or Whitlam

realised. If only Barack Obama and Julia Gillard

were more like them.

Canberra, under Robert Menzies and later

Bill McMahon, put support for the Vietnam

War squarely in an anti-China context. Whitlam

challenged this view, believing Australia

should seek good relations with all four powers

dominating Australia’s region: the US,

Japan, China, and the Soviet Union. Taking a

risk, Whitlam announced his appeal to Beijing

for a visit before he even telephoned me to try

to seek an invitation! McMahon denounced

Whitlam’s gambit as naive.

I knew the French ambassador in Beijing,

Etienne Manac’h, from conversations in Paris

about Vietnam while writing for the Atlantic

Monthly. I explained to him that Whitlam’s

views on Vietnam and China were close

to France’s. Could he smooth Whitlam’s path

to Beijing? Manac’h was enthusiastic and soon

involved Premier Zhou Enlai; at Harvard

I received a cable from Whitlam’s office,

‘Eureka. We won.’ The opposition leader

headed to Beijing.

Whitlam needed the emerging Nixon-Mao

entente against the Soviet Union as a framework

for Labor’s attempt to give Australia an

updated position in Asia. But he was slow to

grasp the strategic shift in Chinese thinking

from 1969. The night we met Zhou, the premier

criticised John Foster Dulles for his 1950s

policies of ‘encircling China’, then added,

‘Today, Dulles has a successor in our northern

neighbour.’

Whitlam said, ‘You mean Japan?’ I realised

with horror that Gough failed to see Zhou

meant the Soviet Union.

Zhou was curt: ‘Japan is to the east of us –

I said to the north.’ Indeed, it was hard for

anyone on the Australian Left to accept that

Mao and Zhou might consider the Soviet

Union an enemy.

Two weeks after the evening with

Zhou, I was driving through the streets

of the silk city of Wuxi in the Yangzi Valley

when the car radio said in Chinese that

Henry Kissinger had just finished secret

talks with Zhou, and Nixon would be visiting

China the following year. Whitlam

was delighted. McMahon gnashed his teeth.

Mao, ill with congestive heart failure, was

excited at Nixon’s arrival. In preparation,

he had his first haircut in five months. Rising

early on the day Nixon was due, dressed

in a new suit and shoes, he pestered Zhou

with phone calls on Nixon’s exact movements

from Beijing airport.

‘Our common old friend, Chiang Kai-shek,

doesn’t approve of this,’ the 78-year-old dictator

said to Nixon, gripping his hand for a full

minute. ‘I like rightists,’ he remarked.

The Nixon-Mao compromise had three

ingredients: a focus on the Soviet threat;

a modus vivendi on Taiwan in which China

got the form (‘One China’) and the US

got the substance (ongoing ties with

Taiwan); a tacit agreement to disregard

ideological differences.

Nixon declared on his way home, ‘That was

the week that changed the world.’ His deal with

China did change the world of the 1970s, and

Whitlam’s relationship with Zhou helped, but

subsequent events undermined the Nixon-Mao

compromise: the collapse of the Soviet Union,

the coming of democracy in Taiwan, giving the

island a sense of itself as independent, and the

Tiananmen Square tragedy of 1989 that ended

the convenient denial of ideological differences

between China and the US.

Since the late 19th century, the US had

difficulty in maintaining decent relations

with Japan and China simultaneously. Dramatically,

however, the Nixon-Mao summit

indirectly ushered in a tripartite equilibrium

between Japan, the US and China, created

by America’s lead, with peace for all three

lasting more than 40 years. This has been the

umbrella under which Asia Pacific has prospered.

It is the fundamental guarantee of Australia’s

security.

Any multipolar alternative to the tacit USled

security system, with spokes out to Japan,

South Korea, Australia and others, would be

unstable and dangerous. The relative decline

of the US does not obviate American leadership

in East Asia, any more than its relative

decline in the 1950s — as Germany, Japan, and

Britain recovered from the second world war

(spurred by the US economy, as China’s rise

is today) — obviated its leadership in NATO,

East Asia and beyond for half a century.

Unfortunately, today, Obama and Gillard

lack a sense of history, eschewing Nixon’s

geopolitics while being half-hearted

about Whitlam’s liberal internationalism.

Obama is backing away from American leadership

and proposing to reduce US military

strength, hoping nasty regimes will follow suit;

this has never worked.

Gillard, like Obama, has excessive faith in

multilateral processes and international paper

covenants. Both hint that national sovereignty

is outmoded, evidently taking a lead from

European social democracy. But as the EU

sails hopefully into transnationalism, East Asia

is different. Beijing has an old-fashioned view

of sovereignty and uses international institutions

only to ward off difficulties for China.

Nixon told Mao: ‘What is important is not

a nation’s internal political philosophy.’ Yet

today in US-China and Australia-China relations,

domestic values are extremely important.

Democracy enters the picture as it never

did for Nixon and Whitlam.

Tomorrow’s Chinese political system is

unknown. In the US, Australia, France, Japan

and other democracies, despite uncertainties,

the political process is a given. Not so in

Beijing. In 1971 we knew the China we were

dealing with was repressive, far weaker than

the US, and passive except for its anti-Sovietism.

In 2011 its political-economic system is

an unprecedented hybrid market-Leninism.

It holds its cards close to its chest, but how it

plays them matters almost as much as how the

democracies play theirs.

Domestic American realities also count.

Obama’s commitment to US supremacy in

a time of austerity is in doubt. In Australia-

China relations, too, ‘internal political philosophy’

matters, as Stern Hu and the Melbourne

Film Festival found out last year. Beijing’s

hardcore types do not understand how the

press and other non-government units operate

in a democracy.

One hopes American leadership continues,

but it won’t be through Obama’s embarrassment

over US power and chatter about moral

equivalence. Obama slights the notion of

clashes of interest and values among nations.

He talks with everybody about nothing and

with nobody about anything. Such mushiness

could shrink US power.

Forty years on, the China challenge is

more complex than for Nixon and Whitlam.

But it can be safely handled by strong

and self-confident American leadership, in

cooperation with Japan, Indonesia, Australia,

South Korea, Vietnam, India and other

powers wary of China. We don’t know what

fresh security arrangements may replace the

US-led system in Asia, but they sure as hell

haven’t appeared yet.

Beijing is ambitious yet often patient and

far-sighted. It will exploit any naivety, inattention

or lack of spine shown by the democracies,

but almost unfailingly it respects superior

power. Probably, the Chinese leaders know

the US is more resilient than believed by militant

generals in the PLA and hyper-nationalistic

young Chinese firebrands, or by the US’s

own pessimistic intellectuals.

Ross Terrill is a research associate at Harvard’s

Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies.

Lost leaders

Forty years on, where is the farsightedness

that characterised Whitlam’s visit to China?

ross terrill

Spectato r Australia

The Autumn 2010 issue of "WILSON QUARTERLY" cover story is Ross's article “WHAT IF CHINA FAILS?”

Final paragraph reads:

"I HOPE FOR A MEASURED RISE OF CHINA THAT BALANCES ECONOMIC GROWTH WITH POLITICAL FREEDOM; THAT TAKES PAINS TO ACHIEVE GIVE-AND-TAKE BETWEEN CHINA'S SINGULAR CULTURE AND OTHER ASIAN AND WORLD CULTURES; THAT APPRECIATES THE 21ST CENTURY WORLD AS AN INTERLOCKED WHOLE, WITH LITTLE VIRGIN SPACE FOR A NEW HEGEMON TO PLANT THE FLAG; THAT RESTRAINS ITS MILITANT GENERALS IN THE PLA AND REJECTS HYPER NATIONALISM; THAT IS CAUTIOUS ABOUT ITS APPARENT LOOMING TRIUMPH, BECAUSE THE U.S. IS MORE RESILIENT THAN BELIEVED BY EAGER CHINESE NATIONALISTS AND THE U.S.'S OWN PESSIMISTS."

Aussies Vote

August 16, 2010

With Friends Like These

How not to gain China’s respect.

Vol. 15, No. 25, March 15, 2010

Puncturing The Echo Chamber

Kennedy's seat has been returned to the people.

11:25 AM, January 21, 2010

Obama Blunders Through Asia

Undoing Bush's years of deft diplomacy.

Vol. 15, No. 11, November 30, 2009

The Empire Strikes Back

China tries to suppress its minority problem.

Vol. 14, No. 42, July 27, 2009

Aftershocks

A new China could be glimpsed after the earthquake.

Vol. 13, No. 38, June 16, 2008

Mao's Madness

When the Great Helmsman declared war on his people.

Vol. 12, No. 26, March 19, 2007

Bush's String of Firecrackers

From the March 28, 2005 issue: Time for some democratic noise in East Asia.

Vol. 10, No. 26, March 28, 2005

Awesome Aussies

An extra-special relationship.

Vol. 9, No. 03, September 29, 2003

BEIJING VS. TAIPEI

Vol. 4, No. 47, August 30, 1999

Why I Write: Ross Terrill

Why I Write

Friday, 12 February 2010 08:02

Written by JFK Miller

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In 1946, George Orwell wrote an essay entitled Why I Write detailing the forces which compelled him to put pen to paper. In this, our continuing Web series, we talk to China authors about their literary habits and reading preferences, and examine Orwell's question which lies at the heart of being an author – why they write

Dr. Ross Terrill is associate in research at Harvard University's Fairbank Centre and author of Mao: A Biography, Madame Mao, China in our Time and, most recently, The New Chinese Empire.

Why I write

To crystallize my thoughts, to experience the delight in turning out a good sentence, to enrich readers and hear their satisfaction with my books and articles

Do you write every day? If so, how many hours?

I am not happy if I don't write every day. Sometimes I miss because a chapter or an essay is just finished and I am researching the next, or because I am traveling. I write only in the mornings. Best is to grow straight to the keyboard upon getting up, then my mind is clearest

Worst source of distraction?

Noise. Suddenly remembering tasks not done - the solution to this is to make lists, instead of letting stuff jump into your head as a distraction

Best source of inspiration?

Get truly inside the topic you're writing about. Then anxiety turns into pleasure. A few sentences done nicely brings on inspiration for later sentences.

How often do get writers' block/doubt your own ability?

Don't know what writer's block means. It doesn't exist for me. I don't doubt my ability but I agonize over my relevance, or the relevance of what I am presenting to readers. Tastes are various, time is limited, priorities press in on people, what do they know, care, or want to know about China. How can I engage them, and not bore them, that's what I wrestle with.

Contemporary writer in any medium who you never miss?

Charles McCarry, the spy and political novelist, author of Shelley's Heart and other books about Washington. Among columnists in the USA, I never miss Charles Krauthammer, sharp, witty, well-informed.

Favorite Chinese writer?

Two recent Chinese books have pleased me. Ying Ruocheng's autobiography Shui liu yun zai is charming, sad, amusing, informative about Chinese culture and politics. Also a literary book, Xian shun xian hua (Random Thoughts on Idle Books), recently published in Guilin, by the Chinese-American Zhu Xiao Di, which shines with a love of literature and China's best values.

Best book about China?

Read together, Han Feizi for his basic wisdom about human nature, and Mencius for his sunnier view.

Favorite book? Favorite writer?

Marcus Aurelius's Meditations, for he gets life correct.

The book you should have read but haven't?

Thousands.

You look back at the first thing you had published and think...

A six-part series I wrote in Rupert Murdoch's The Australian newspaper a few months after my first China trip in 1964. Murdoch personally pruned my articles with a blue pencil and wrote out the payment check with a fountain pen. I am rather pleased to look back at what I said 45 years ago:

"All around the world, from Singapore to San Francisco, you can see pockets of Chinese society. But only in China can you behold the vast and formidable civilization in its power and its old and beautiful setting. Only in China do you realize what the Chinese as a race and a nation must increasingly mean in the pattern of future decades. Just as once in the past, long before the present barren era of clashing ideologies and wrenching divisions, China was the greatest power on earth, so in the future she may become so again."

How did you get started writing?

Keeping a diary of travels my father took me on around the Australian countryside, of books I read, of my boyish reflections on God and man - that got me started. Soon vanity pushed me to publish.

Does writing change anything?

Of course it does. The Bible, the Koran changed history. Solzenyitzen said a great writer in an authoritarian country is like an alternative government. To a degree that was proved in Moscow.

What are you working on now and when is it out?

A novel, The Moon is not Rounder Abroad, which is a China-America love story. A history of eight decades of US dealings with the CCP from Yanan years to Hu Jintao. And a memoir of my involvement with China, Wo yu Zongguo, which Renmin daxue chubanshe will bring out this year.

[SHANGHAI, MARCH, 2010}

Mao Fever and the Story of a Mao Book

February 26, 2010 in Mao, Watching the China Watchers by The China Beat

By Ross Terrill

When Mao died I wrote: “China does not have, and does not need, a real successor to the bold and complex Mao. Now the revolution is made, another Mao would be as unsuitable as a sculptor on an assembly line” (Asian Wall Street Journal, 9/10/76). I ended the first edition of my biography of Mao in 1980 with the expectation: “‘Raise High the Banner of Mao Zedong’s Thought,’ cry official voices now that Mao is safely in his crystal box. Up it goes higher and higher, until no one can read what is written on its receding crimson threads” (Mao, Harper & Row, 1980, p. 433). For eight years after its American publication and editions in six foreign languages, Mao was never mentioned by the Chinese press. In 1981, when a delegation of Chinese publishers came to New York and my publishers showed them the book, the Chinese fingered it gingerly like a teetotaler shown a bottle of whiskey. The book was well received and I thought that was the end of my attention to Mao; I turned to a study of his widow (Madame Mao, Morrow, 1984). But I was wrong about Mao’s life after death.

In 1981, after five years of deafening silence about Mao, the CCP reassessed him in its “Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party.” Each major nation that experienced dictatorship in the 20th century emerged in its own way from the trauma. Japan, Germany, Italy, even Russia departed sharply from systems that brought war and/or repression. By contrast, China was ambiguous about Mao. Although Mao’s portrait and tomb still dominate Tiananmen Square, Mao himself has floated fairly smoothly into an a-political zone. One must give some credit to the 1981 Resolution for this delicate, if incomplete, evolution.

I said of the Resolution that if the Chinese leadership “delivers on its promises to modernize, and if the growing aspirations of the one billion Chinese people for a higher standard of living begin to be significantly met, the current Delphic dissection of Mao [in the Resolution] may well solidify into history’s verdict on him” (Newsday, 7/22/81). This seems to be happening so far.

But, surprisingly, there occurred a revival in China of Mao studies. Its intellectual kernel was fresh research on Mao undertaken during the 1980s. As a result of a loosened ideological straitjacket, some formerly “banned” aspects of Mao could be investigated. It turned out that the 1981 Resolution gave a green light to work on Mao’s life. As former Mao assistant Li Rui remarked, the Resolution “was not the end but the beginning of research on Mao Zedong” (Li Rui in Xiao Yanzhong, ed, Wannian Mao Zedong, p. 2). Memoirs by military figures and Mao staff members, biographical studies of senior figures, and selective issue of Party documents added to the knowledge of Mao’s actions and words.

To one bodyguard, Li Yinqiao, Mao had made a remark which perhaps explained why readers came to possess memoirs by Mao’s personal staff. “Yinqiao,” Mao said, “the affairs of myself and my family may deceive heaven and earth, but they cannot deceive you.” He added: “You must not write anything about me while I am alive. After I die, you may do so — but you must write the truth” (Li Yinqiao, Quan Yanchi compiler, Zou xia shen tan de Mao Zedong, p. 1; Mao said this after Li had witnessed a quarrel between Mao and his son Anying).

Readers of the new literature of the 1980s learned the human side of Mao: his farmer’s taste in food, his insomnia, his tears at the failure of the Great Leap Forward, his habit of falling asleep with books all over the bed, his desire for young women in lonely later years, his request for songs of the Song Dynasty to be played during an operation to remove cataracts from his eyes in 1975; and so forth (Zou xia shen tan de Mao Zedong, p. 217).

All this did not alter the overall picture of Mao I drew in the first edition of Mao in 1980, but it subtly changed Mao’s image within China. By 1988, some candid reappraisal of Mao’s faults appeared in the press. The Communist Party marked the 95th anniversary of his birth in December of that year with an article in People’s Daily that for the first time in official print contained admissions by Mao himself of his serious errors. Guangming Ribao ran an article detailing Mao’s grave health problems — including a respiratory ailment due to his smoking — from the spring of 1971 until his death. The fresh attention to Mao was low-key and factual. It stressed his human side, both charms and foibles.

***

In Chinese society, departures from Maoism and adoption of Deng-style modernization multiplied. In the later 1980s, a spirit of individualism arose among urban youth. Mao as a young man wrote passionate articles about the individual’s “freedom to love” that old China had denied and new China would guarantee. But for the later Mao, securing the wealth and power of the Chinese nation took preference over the individual. By the late 1980s a cosmopolitan urban generation’s individualistic thinking culminated in the pro-democracy movement of 1989. Unfortunately, a revival of faux Maoism occurred after June 4, complete with a barrage of Mao quotations and a revival of the Lei Feng myth. However, this was aborted by the collapse of the Soviet Union and Deng Xiaoping’s ensuing decision to promote stock exchanges, make his nan xun (“southern tour,” 1992), and cancel the leftist surge.

A fundamental reduction of political tension over Mao achieved by the 1981 Resolution seemed proved when a powerful “Mao re” (Mao fever) of the early 1990s produced a cultural, good-humored remembrance of the former leader. Sometimes the use of Mao was commercial, as if money had replaced memory. Sometimes it was superstitious, satiric, or nostalgic. Seldom was it politically earnest. This Mao re, in fact, signified that Mao’s strictly political leftism was no longer on the table.

Karaoke clubs saw young people enjoying songs in praise of Mao. One pop music cassette called “The Red Sun,” whose lyrics made use of Mao’s slogans, sold six million copies during 1991-92. For many people the music suited their mood of detachment from public life; they could let Maoist lyrics flow over them while simply enjoying the beat of the music.

To sing Mao’s words to pop music, or do business under a portrait of Mao, was a way of regaining one’s spirit after years of amnesia. The Mao fever was like a long-delayed funeral ceremony, remembering one whose enormous connection with daily life had gone, but whose image could never leave the consciousness of anyone who had lived in the Mao era.

***

To my surprise, in early 1989, a publishing house, Hebei renmin chubanshe (Hebei People’s Press) found the tide of interest in Mao sufficient to bring out a virtually complete Chinese translation of my biography.

During the turbulent spring of 1989, I was visited in my Beijing hotel room by its translator Liu Luxin. He brought a copy of Mao Zedong Zhuan (Mao’s title in Chinese) and news that the book, released only a month before, had sold 50,000 copies. Articles appeared all over China, reviewing the book and commenting on its place in a growing “fever for Mao” (E.g. “Mao Zedong re” in Xin xi ribao, 7/11/89). Readers of Mao had told Liu Luxin at the Tianjin Book Fair, just held, of their excited discovery in the book of aspects of Mao’s personality and his relationships with people high and low previously unknown to them.

A cadre in the Yangtze Valley wrote to the publisher: “If this book were to be done by a Chinese, the outcome would inevitably be either too much passion for Mao, or an excessive attack on Mao. But I am astonished by the author’s penetrating analysis and original ideas, particularly his conclusions about Mao.” A former factory manager in Tianjin wrote: “After reading your Mao, I decided to give up my high, admired post, and do something ‘useful.’ I have become an entrepreneur.”

A common chord in the stream of comment was that it took a foreigner to bring objectivity and a human dimension lacking in Chinese writing about Mao. “This foreign writing of biographies of our leaders is a good thing and a stimulus,” said a reviewer in Liberation Daily of Shanghai. “What I hope is that now a Chinese writer will tackle Mao” (Jiefang ribao, Shanghai, 1/23/91). In fact, of course, this was already being done.

The articles, reviews, and letters were not without criticisms, but the remarkable thing was the relatively open comment, praise, and colossal sales of the book. (Commentary on the book included Xin xi ribao, Wuhan, 7/11/89; Wenhui dushu zhoubao, Shanghai, 9/1/90 and 9/22/90; Dachao xinqi: Deng Xiaoping nanxun qianqian houhou, p. 106; article by Situ Weizhi in Xinhua wenzhai, 1990/1; and Hebei ribao, 6/22/89). Eventually, by early 1997, about 1.2 million copies had been sold up and down China, a higher total than for any other book from the same publisher for years.

For one act I owe enormous gratitude to Hebei People’s Press, at least to the bold editor of my book, Wang Yaming (since departed from the firm). Permission from the party-state to publish Mao had been achieved on the understanding that the book would be faxing nei bu (for restricted sale). But at the last moment Wang went to the printer and had those four characters removed from the plates. The book went out to Xinhua and other stores as a regular book. This could never have happened in Beijing and, without the editor’s bold step, the book’s future would have been modest.

Unfortunately, despite Wang’s initiative and the publisher’s fluke success in the marketplace, Hebei People’s Press was an old-line state firm with no use of contracts and limited editorial professionalism. Many readers complained about the translation. My own frustrations with the house mounted.

For several years they would periodically invite me to Shijiazhuang for banquets and TV interviews and at the final dinner press into my hand an envelope with maybe 20,000 RMB, maybe 30,000 RMB. One year, they sought to reward me and themselves with a suggestion. The publishing house needed a new car but prices, due to tax, were terrible for a foreign car. Would I buy one in Boston, export it to Hebei, and take a commission on the money they would save by avoiding (they hoped) the Chinese tax? I explained I was a writer, not a car dealer, and the matter was dropped (I wrote of this experience in the New York Times Book Review, 5/26/96).

After China signed the Berne International Copyright Convention in 1993, this decrepit approach came under severe pressure. A simple contract was finally signed between Hebei and myself and the book continued to sell. But the corruption of an old-line firm used to doing business by winks and nods was deeply entrenched. They sent no royalty statements and paid no money. Eventually one of my former students, then doing business in Shenzhen, negotiated a settlement with them. In the course of the talks, Hebei People’s Press claimed the number of copies printed — always, of course, included at the end of a Chinese book — was a misprint and the actual number was 450,000 lower than stated. My former student threw up his hands at the duplicitous behavior.

Writing about Mao remained a sensitive matter in Beijing. “False Biographies are Now Forbidden” was the title of a Xinhua release in 1993. Only “accurate, serious, and healthy” works would henceforth be permitted. During 1992, the State Press and Publications Office complained that thirty-seven unworthy books had been published without authorization (Geremie Barmé, Shades of Mao, p. 30). Unsettled ambiguity about Mao remained and it increased under Jiang Zemin’s influence.

Foreign China specialists, including me, overestimated the crisis China would face with Deng’s death (Terrill, Oped, New York Times, 2/20/97). In fact, the event was not at all like Mao’s death. China’s political system had matured in the two decades between 1976 and Deng’s death in 1997. “Mao-as-an-institution” had given way to a quite different kind of CCP leadership. There was not in February 1997 the stunned uncertainty that had existed in September 1976.

***

China Renmin University Press approached me in 2003 to seek a contract for re-publishing my Mao in Beijing. Recent years had seen a poor performance by Hebei People’s Press with its 1989 edition (they had meanwhile brought out a translation of my Madame Mao in a restricted edition) and I was contractually free to sign with China Renmin University Press. But I had low expectations. Surely the Chinese had read enough about Mao already? Official biographies of Mao had come out, and Philip Short’s biography had also appeared in Chinese. Moreover, China Renmin University Press was an academic outfit, and I did not expect substantial sales. I was wrong.

One reason I was happy to see the book in Chinese in Beijing was that the Stanford University Press edition, which had supplanted the Harper and Row and other editions from 2000, was forty percent new. Much fresh material had become available. This made the China Renmin University Press edition far superior to the Hebei People’s Press edition. However, China Renmin University Press declined, with my eventual approval, to include the new Introduction that began the Stanford revision; it was an account of Western sinology’s handling of Mao over the years.

Renmin brought Mao Zedong zhuan out in the spring of 2006, together with six other foreign works relating in one way or another to Mao. It was a handsome volume, in red with 200 photos. The head of the house, Professor He Yaomin, was disdainful of the cover of the Hebei edition. “All black, with a statue of Mao’s head in Stalin style,” he sniffed, holding it up at our meeting. China Renmin University Press printed 8000 copies of my volume.

Xin Shiji zhoukan (New World Weekly) soon wrote: “With this biography new Mao fever has come upon China.” At a single store, Xidan tushu dasha (Beijing Book Palace), the title sold 1500 copies in two months. Renmin quickly reprinted it four times. The book was a best seller in the category of biography and memoir in shops in many cities. Said Sui Guoli, the sales manager at Beijing tushu dasha: “It’s unusual for such an academic biography to sell so well, especially as most buyers are individuals, not government units” (Xin Shiji zhoukan, p. 19). This popularity continued in 2007.

The series editor at Renmin, Pan Yu, told Xin Shiji zhoukan, “We just didn’t expect this success. We are a higher education publisher, doing high quality material and high quality writing. We weren’t quite prepared for this boom.” The editors had to scurry to organize successive re-printings. A Ms. Zhang at the Zhongguancun book store was cited in several media with a shrewd remark: “The young are buying Ross Terrill’s book in order to understand, and the old in order to remember.”

On the 30th anniversary of Mao’s death in 2006, the well-known writer Zhang Xiaobo looked back at September 9, 1976, when he was a boy of 12. “I was so shocked at the news. We had been educated to believe Mao was a god, someone no one can profane, who would never die. Adults may have been prepared, because of his old age. But we kids weren’t. We just collapsed” (South China Morning Post, Magazine, 9/9/2006). Thirty years later, Zhang, the co-author of China Can Say No, compared the Mao era with the post-Deng China of 2006. “With Mao, we trod the road of faith. After Mao, we tread the road of doubt. The road of doubt is better than the road of faith, but doubting has twisted human relations. We don’t believe each other.” Mao was still a measuring rod to assess where China had gone since 1976.

The other six foreign academic works on Mao and CCP history in the China Renmin University Press series were all good books, but they did not sell like Mao Zedong zhuan. One reason may lie in aspects of the nature of biographical art. My book is just Mao’s story. A biography has to make its subject believable in order to grip people. Yes, the subject of the biography may have made grievous mistakes. But even in that case the reader must feel the subject as a human being. He must be led to understand why that person did what they did. He has to be shown the context. Mao made history; at the same time history also made Mao, both Chinese history and world history. Mao was not a disembodied spirit, who came down upon China from the clouds.